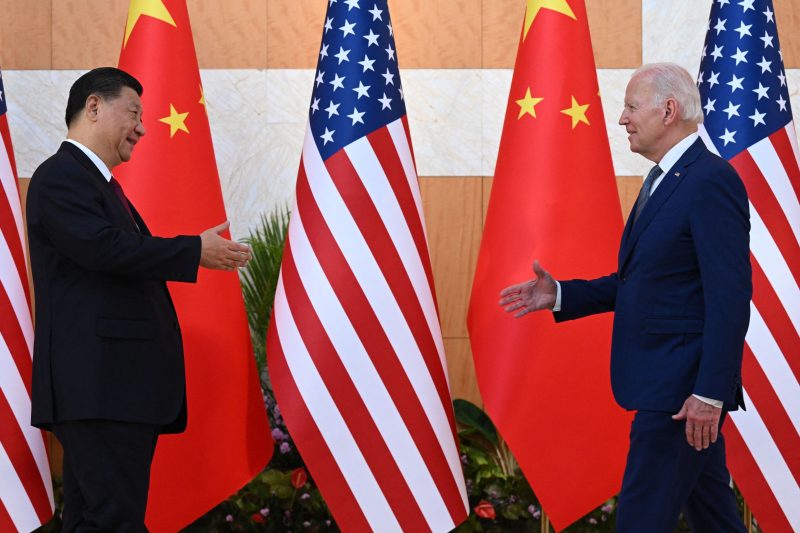

President Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping are set to meet face-to-face Wednesday in a high-stakes summit that both countries hope will help thaw the U.S.-China relationship and reestablish stronger lines of communication after a series of disputes since the two leaders last spoke about a year ago.

Biden and Xi have not held any phone calls since they sat down face-to-face at a summit in Bali last year, a notable shift from the multiple calls the two leaders held leading up to the Bali meeting. Since then, the relationship has endured myriad difficulties, including the discovery of a Chinese spy balloon flying over the continental United States that temporarily scuttled a planned visit to Beijing by Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Neither U.S. nor Chinese officials expect significant agreements or policies to come from Wednesday’s session, which will be held in the San Francisco Bay Area on the sidelines of an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. U.S. officials have signaled they believe the two countries could soon resume military-to-military communications, which were suspended after then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) visited Taiwan in August 2022. But in a signal of the frostiness of the relationship, U.S. officials said Biden and Xi will not put out a joint statement after the meeting — a step world leaders usually take after such sit-downs — instead leaving each side to release its own readout.

High-level officials in both the United States and China see the relationship as one of competition, and one of the goals of the Biden-Xi meeting is to figure out how to responsibly manage it. Despite numerous points of contention, both Biden and Xi have reason to try to thaw the relationship. Biden has long feared that a misstep could lead to an escalation that neither side wants, and U.S. officials stress the need for the two countries to have an open line of communication to guard against this eventuality.

That is a relatively modest if important goal. “We’re a long way from the days of major summitry producing joint outcome documents with long lists of deliverables,” said Rick Waters, a former State Department China coordinator.

Waters, who is now managing director of Eurasia Group’s China practice, said the meeting is probably an effort to continue a process begun in Bali: to “set a floor” for the relationship, establishing communication channels that could help avoid an unintended conflict.

The Biden administration has identified China as the United States’ most significant long-term strategic challenge and has prioritized building relationships with countries in the Indo-Pacific region to create a bulwark against Beijing. China has taken note of strengthened U.S. partnerships with countries such as Japan, Australia, India and Vietnam, and feels threatened by them, U.S. officials say.

Even if military-to-military dialogue is restarted, the “deeper, more profound problem” from China’s point of view is what it sees as American military provocations and encroachment on its interests in the Asia-Pacific region, said Da Wei, director of Tsinghua University’s Center for International Security and Strategy in Beijing.

That includes Washington’s routine military surveillance flights and “freedom of navigation” voyages through international waters and airspace, he said.

“From China’s perspective, the U.S. Air Force and Navy are infringing on China’s interests,” said Da, a professor of international relations. “When the U.S. tries to sail through the Taiwan Strait, that’s a political gesture.”

Despite Biden’s concern about China, the president has had to expend considerable time, energy and political capital on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and, more recently, Israel’s military campaign in Gaza in retaliation for the Oct. 7 Hamas attack. The president’s aides say the administration nevertheless remains focused on the Indo-Pacific region and pointed to recent travel there by top Cabinet members.

But the war in Gaza has clearly consumed much of Biden’s time recently as U.S. officials pledge to support Israel in its goal of eliminating Hamas and simultaneously seek to keep the conflict from escalating into a major regional conflagration. It has also tested U.S. relationships abroad, as Israel’s aerial bombardment has hit civilian infrastructure such as hospitals and refugee camps, killed more than 11,000 Palestinians, and forced more than 1 million Palestinians to flee to southern Gaza. Israel said it is targeting Hamas compounds that are underneath hospitals and embedded in the civilian population.

The United States is especially worried about potential escalation by Iranian proxy groups, particularly Lebanon-based Hezbollah on Israel’s northern border. Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser, told reporters that Biden will address the Middle East in his meeting with Xi, urging China to add its voice to those cautioning Iran against inflammatory action, because China and Iran have recently bolstered their diplomatic relationship.

“President Biden will make the point to President Xi that Iran acting in an escalatory, destabilizing way that undermines stability across the broader Middle East is not in the interests of [China] or of any other responsible country,” Sullivan said. China, he added, “has a relationship with Iran and it’s capable, if it chooses to, of making those points directly to the Iranian government.”

The meeting marks Xi’s first visit to the United States since 2017, when he sat down with President Donald Trump at his Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida. U.S. officials took exceptional measures to ensure the meeting was carefully choreographed, as Chinese officials sought assurances that Xi would not be embarrassed by the kind of protests or public challenges that he rarely faces in China, where his Communist Party maintains a tight grip.

Chinese officials at the time, for example, wanted to know details including how many steps Xi would have to take before taking his seat in the meeting room, and they sought certainty that Xi, who seldom travels outside of China, would receive the respect he is accustomed to.

Chinese officials are similarly on guard against any potential embarrassment to their leader during this visit, experts said.

“It is part of this concern that Xi might look left out at this big event that the U.S. is hosting if there are significant announcements” about a Biden initiative called the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, of which China is not a member, said Patricia Kim, an East Asia scholar at the Brookings Institution.

The two sides are expected to address several contentious topics, including human rights, the South China Sea, Taiwan elections, Chinese interference in U.S. elections, Russia’s war in Ukraine and guidelines for artificial intelligence.

“I don’t think this is going to be a meeting that produces some new grand bargain for major deliverables,” said Michael Froman, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, who served as President Barack Obama’s U.S. trade representative. “To a certain degree, the meeting itself is the deliverable.”

The APEC summit comes at a difficult moment for China, which has been facing economic turmoil, and Xi is expected to attend a dinner with CEOs after the meeting with Biden to assure them that China is open for business.

Some Republicans argue that Biden’s meeting with Xi is coming at too high a price. While the president is seeking to show that he and his team can responsibly manage the China relationship, Republican hawks in Congress have criticized the administration as insufficiently tough on Beijing.

A group of lawmakers sent a letter to Biden last week accusing the administration of catering to China to get it “to the table” and demanded that the president extract specific commitments from Xi, including agreements to release wrongfully detained U.S. citizens and cease unsafe intercepts of U.S. vessels and planes.

Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Tex.), chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, criticized Blinken and Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo for what he described as concessions to China during trips there in recent months. “You don’t make concessions to get a meeting,” McCaul said.

Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wis.), chairman of the House select committee examining the U.S. relationship with China, said that there may be an upside to the Biden-Xi meeting but that China has exhibited worrisome behaviors in its effort to overtake the United States economically, militarily and geopolitically.

“There’s some good that could come out of it that I can sort of squint and see,” Gallagher said. “But I just am very skeptical, because the Chinese Communist Party just continues to get more aggressive.”

Nonetheless, with Biden grappling with conflicts in the Middle East and Europe and a reelection campaign at home, and Xi facing major economic challenges, both leaders would benefit “domestically and internationally” by showing they can hold a productive meeting, Da said.

“If they have a successful summit,” he said, “that will send out a constructive signal to the whole world.”

Theodoric Meyer contributed to this report.